All About Pheasant Hunting

I was fortunate to grow up with a gun in my hand, having my first shotgun before I was in first grade. It was a Mossberg bolt-action .410 bore, it was to me at the time a massive beast, and although I carried it out to the dove field, my Dad carried it back to the car every night, every single night as he liked to remind me. Sure, I could make that old Mossberg go bang, I could break clay pigeons, but shouldering it was a struggle. I had no effect on the dove population whatsoever.

The next shotgun was a double-trigger, extractor only, Crescent .410 SxS with a cut-down stock. A .410 bore is a poor choice for just about everything, a spectacularly miserable choice for pheasant hunting, but at least the gun fit me and I could shoulder it. As a result, I bagged my first roosters with it.

When I was a boy, growing up hunting with my father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, the landscape was different. We didn't use dogs, although we had dogs, cats, and ponies as pets, and though we no doubt could have spent less time afield with bird dogs, farms were generally dirty, without being tiled, having wonderfully nasty fence rows and the corn rows were planted far enough apart where we walked standing corn. Pheasants had to fall dead and it was standard practice to shoot them once on the way up and once again on the way down for good measure, as that was the only path to 100 percent game recovery.

Standard fare, back in the day, was 1-1/4 oz. of #6 lead shot at 1330 fps, either Super-X or Peters, and that was about all that was locally readily available. No. 5 shot is noticeably better and in 1984 John Brindle noted that “... British No. 3 (American No. 4) . . . and delivered from tightly patterning chokes is the best bet.” John Brindle further noted that the combination of gun and ammunition should produce 75 – 80% patterns in the 30 inch circle at the farthest usual range the birds are taken at. That isn't just 75-80% of anything, that's 75-80% of a 1-1/4 – 1-1/2 oz. payload.

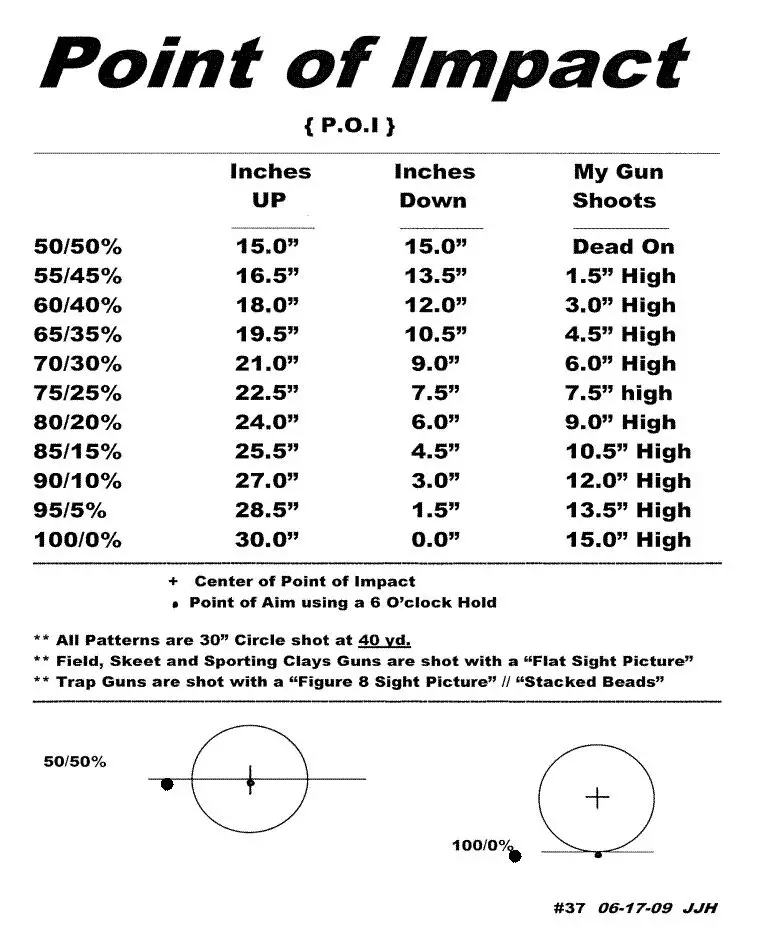

John Brindle also had very clear advice for point of impact, stating that a skeet gun should have its patterns 6 inches high at 20 or 25 yards, a game gun or sporting clays gun should have patterns that are 6 – 8 inches high at 40 yards, and a trap gun not less than 8 – 12 inches high at 40 yards, referring to American rules single target trap. Everyone will eventually decide what they prefer for themselves, but the 70/30 or 75/25 hunting gun has long been standard fare. Jack O'Connor, for example, wrote that 12 inches high at 40 yards, a 90/10 pattern, was the ideal pheasant gun point of impact.

There is solid basis for this approach. We lose about 10% of our pattern for every 5 yards past 40 yards, so that 80% 40 yard pattern may now be a 60% pattern at 50 yards and a 50% pattern at 55 yards. Pheasants tend to rise, so a higher point of impact offers built-in vertical lead and your pattern height drops quickly at extended ranges as well.

The weight of a shotgun gets attention as well, for if you are walking and need to be ready all the time with the weight of the gun on your arms for hours, after the first six or seven miles of walking heavy guns are literally a drag. Somewhere between six and seven pounds is ideal, with 7-1/4 pounds right at the limit for walking all day for most folks.

I was still young, quite young, when I was able to rid myself of the .410 bore curse once and for all in the form of a High Standard Supermatic Trophy 3 inch gas-operated 20 gauge. It fit and it dropped a boatload of pheasants. It was also a generally lousy, extremely low-quality gun, a single-shot more often than not, but one good pattern is a was a lot more than I ever had the chance to work with prior to that. The ideal “learning gun,” again as mentioned by John Brindle and many others, is the gas-operated twenty gauge autoloader. John Brindle wrote, “Trapshooting apart, the best gun to use to teach anyone to shoot with is a gas-operated autoloader in 20 gauge, with a 26 inch Improved Cylinder barrel.” Now that interchangeable screw-chokes are standard, it might be the only gun you ever want or need, except for ugly intervention of steel shot which severely gimps the usefulness of the 20 gauge where lead is not allowed, or if you are unwilling to pay for tungsten loads.

A FEW STORIES AND LESSONS LEARNED

DAD

Old habits die hard, and that was the case with my Dad, who shot a standardweight Browning Automatic-Five (28 inch, plain barrel, Modified choke) for much of his adult life. When I was a kid, Dad often had a pair of roosters on their way down before “junior” got his gun to his shoulder. But, it is difficult to grow younger, and back when I used a 6-1/4 lb. 20 gauge B-80 more than any other shotgun for wild pheasants, the tables were turned. “You were just a quarter second too fast” was something I heard a lot of.

It was 1994, and the “Browning Gold Twenty Gauge” just came out. Dad finally broke down and got one. He liked to “complain” that he spent an extra fifty dollars on it because the one at Mega-Sports fit him better than others he had tried. It needed a trigger job and a better recoil pad, it got both, and the first eleven times my Dad fired that gun while hunting resulted in eleven pheasants that fell dead and that was that. It was easily his favorite and most used shotgun until the day he died. Not just pheasants, but turkey, and it went to Argentina as well. A lighter, faster gun can roll back the clock for you by twenty years.

DAVE AND THE 100 YARD PHEASANT

My buddy Dave is an accomplished marksman, expert gunsmith, and works very long hours at retail. Dave wanted to go pheasant hunting and the day that was available to him was bitterly cold, windy, and there was waist high snow in some areas. It was one of those forlorn days in January, with blown-down cover and generally a sparse landscape. The wind picked up overnight, there was a lot of drifting, but we still decided to go along with the help of Frisco, Dad's Brittany. I didn't expect much action, but you never can tell.

We were walking past a frozen pond and a rooster decided to run across the ice (a comical sight in itself) and hid in a large brush pile. We trudged towards to brush pile, the dog more or less tunneled, and the rooster shot straight up out of that brushpile, flying vertically, snow flying all over the place. Had the rooster just run out of the brushpile on the other side, we never would have seen him, and had he flown away from us there would have been no shot. Dave was actually closer to the bird, I yelled “Shoot! Shoot!” but Dave hadn't bothered to bring his gun up.

I emptied the gun, hitting that rooster three times, his torso blown backward with every shot and he fell deader than snot on the ice with a loud thud. Dave decided that I was crazy, killing a pheasant at “100 or 120 yards,” or so he said. Well, it was a perfectly exposed shot, unusually so, and no, it wasn't 120 yards or even 100 yards. It was every bit of 85 yards, though, and I didn't have the heart to tell Dave I was using 1-7/8 oz. of buffered #4 shot along with my best extended turkey choke. It just pays to be prepared, that's all.

CHRIS AND THE PHEASANTS

Chris is an outstanding shot. Whenever there was race games under the lights, there was Chris. If it was skeet and trap at Downers or sporting clays at Seneca, there was Chris. Even when there was a stop at Des Plaines Conservation area, there was Chris. Chris didn't hunt though, but he was interested. His shotguns were competition guns, but he did buy a lighter, very pretty Beretta 687 just for pheasant hunting. So, I took him pheasant hunting and when bird got up within his range, I didn't shoot. Unfortunately, neither did Chris. “I wasn't ready,” was the refrain. After watching half a dozen healthy but evil Chinese Communist pheasants fly away merrily without a shot being fired, that was that. It is a combination of the “dead gun” syndrome that sometimes goes with premounted target shooting and “he who hesitates is lost.”

THE POS BENELLI

Another friend, a different Dave, wasn't happy. He had just emptied his checking account on a Benelli Ultra Light only to discover it was far too painful to make it through a single round of sporting clays with. Certainly not all inertia guns are quite that brutal, but if you can't stand to practice with your hunting gun it isn't a plus. That BUL was sent packing in a hurry.

THE PHEASANT CONSERVATION KING BERETTA

Brother-in-law Bruce normally did pretty well in the field, as long as he was using his 870 Wingmaster. But, he needed an “upgrade,” and bought a new Beretta O/U with E's and L's in the model name: a beautiful gun.

The problem was the way too flush mounted tang safety, a royal pain to get off with cold or gloved hands. After shooting a hot steaming pile of nothing with his new high-grade Beretta, it was back to the old Wingmaster. Gun fit matters, but so do the controls . . . just as much. Poor gun fit or poor controls will help make you an unintentional expert in pheasant conservation.

FINALLY

We've come a very, very long way from the 1750's fowling gun, a single-shot 16 gauge throwing with a 42 inch barrel. By 1870, though, the popular British gun was a 12 gauge SxS, 7 – 7-1/2 lbs., throwing 1-1/8 oz. payloads for game and 1-1/4 oz. for trapshooting.

The most important factor in selecting a pheasant gun is your personal comfort and your personal confidence. Comfort in the action type, comfort in the reliability, comfort in carrying, comfort in shouldering, comfort with where it shoots, comfort with the pattern it throws, comfort with the controls, comfort with the way it fits you, comfort with normal maintenance, and so it goes. There isn't any correct shotgun or “right” shotgun, there is only what is right for you.

After we get all the comfort stuff out of the way, we can just go hunting.

Copyright 2016 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.