Why Autoloaders Kick Far More Than They Need To: Beware the "Versatile" Shotgun

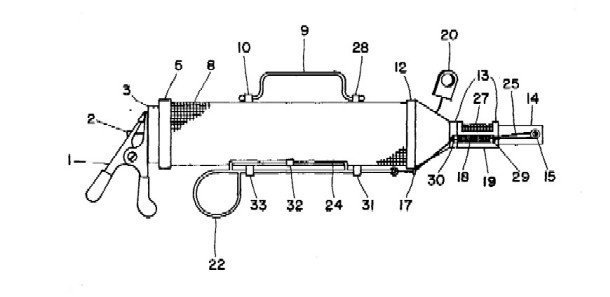

Above, the patented cricket gun, USP #5,103,585 of April 14th, 1992. The cricket is discharged by pulling on the release trigger. This amazing device allows the fisherman to discharge one insect at a time, holding another cricket in reserve (in an isolated chamber) for later use. Thoughtfully, this device is designed to "not injure crickets." The next time you hear that "it is so good it is patented," you might want to consider the wondrous cricket gun. Though apparently very close to a truly "recoil-less" gun, it is decidedly of limited use.

There is an endless fascination with recoil, one that is the never-ending story. It does not have a cute, cozy, or clever answer and it never will. Though there is often lively banter concerning “It Kicks Me, It Kicks Me Not” there is no resolution in sight. Believe it or not, we the shooters are a big part of the problem.

We don't always ask the right questions. You'll hear the hopeful question about a gun or a shell, asking “Does it Kick?” It isn't strictly an honest question. We don't want to really know if a shotgun kicks someone else. What we want to know is if it is going to kick us, not them. We don't know the other person's normal shooting routine, ambient conditions, manner of dress, the loads used, how well a gun may or may not fit them, and so forth. Not only that, they don't know ours. Still we ask, “Does It Kick?” We might as well be asking a stranger how comfortable their clothes are, for all that this impossible question imparts, or perhaps more correctly, “Are your boots going to be comfortable for me when I walk in them?”

Jack O'Connor referred to humans as nervous, quivering blobs of protoplasm. Humans cannot tell temperature precisely without a thermometer, can't tell time precisely without a watch, cannot detect whether a lens transmits ninety percent light or ninety-eight percent light, and we don't know what we weigh exactly without stepping on a scale. We don't have a clue as to our blood pressure or cholesterol levels without instrumentation or testing. Small wonder than humans are incapable of precisely measuring recoil. Ask anyone pulling the trigger on a shotgun what the recoil force was in foot pounds or what the recoil velocity was in feet per second and you won't get it answer. We just don't know and we can't say. We can't precisely feel the recoil event at all. We react to it, of course, but long after it happens.

Autoloaders kick far more than they need to. The reason is what we think we want out of an autoloader. We think we want versatility. Maybe we do, but versatility comes at a price. Shotshell function is not at all a constant. When we change shells, we change everything. A 2-3/4 inch unfolded length twelve gauge might throw 7/8 oz. of shot, it might throw 1-1/4 oz. or 1-1/2 oz. of shot, or it might be as light as a 3/4 oz. payload. Yet, all are SAAMI or CIP shells that necessarily function within established guidelines.

In the example of a gas-operated autoloader, how does a gun manufacturer design gas port geometry for proper function of all these different shotshells? Note that we haven't even considered three or three and a half inch shells yet, we are still discussing only 2-3/4 in. hulls. In many ways, they cannot anymore than the ideal suspension system for both smooth road and off-road vehicle use exists as just one thing. Gas flow through ports and valves varies by shell, it varies by temperature, and the ideal bolt speed varies by cleanliness of the system, tolerances of the system, and so forth.

Gun manufacturers know what people grouse about the most, though, and that is jamming. This gun jams is the universal cry that can give a gun a bad name, even though it may well be user error more than the gun. Perpetually fascinated by things that don't move when we would like them to, the autoloading shotgun enthusiast is fascinated with jams. No, we don't know how to clean our guns properly and no, our reloads don't really look a lot lot shotgun shells. It doesn't matter, though, because the gun is a jam-o-matic and we just hate that.

Since we can't figure out what shells we want to use and happily ignore what we are supposed to use, manufacturers have had to compensate. They have done just that, using far larger gas ports than ideal which make autoloaders cycle far, far more violently than necessary. Rather than a 250 inch per second bolt speed, autoloaders often run at 400 or 450 inches per second bolt speed. The result of this is exactly what we might think we want, or what marketing departments tell us we want: the ability to shoot pipsqueak loads. Often, perhaps too often, you'll hear that a 12 gauge autoloader does not kick with “7/8 oz. reloads.” This type of declaration is stunning, at least to me, as no 12 gauge I have ever shot in my lifetime has punishing recoil with 7/8 oz. loads, much less a gas-operated autoloader. I'm trying to remember if any gas-operated 20 gauge has ever had significant recoil with 7/8 oz. shells and I can't think of a single one. A 7/8 oz. payload is, of course, not only a traditional 20 gauge load, but a 20 gauge “low brass” or light load at that. Why anyone would want to needless give up an additional 12% of their pattern by using a 7/8 oz. load rather than a 1 oz. load escapes me. I don't, the doves taken this year were all from heavier loads, just like every previous year whether it is a 20 gauge or a 16 gauge, much less a 12 gauge.

While versatility is touted as an advantage, it isn't always so. Versatility means compromise. In the case of a 12 gauge autoloader that runs with 7/8 oz. loads, it means unnecessarily high bolt speeds and unnecessarily violent ejection with 1-1/4 oz., 1-3/8 oz., and 1-1/2 oz. 2-3/4 inch loads. The crescent wrench isn't the best wrench as a matter of course, nor is a more versatile shotgun the best or most enjoyable shotgun for the application. Compromise detracts from what could have been. The most enjoyable quail gun, the pheasant gun, the rabbit gun, and the deer gun will never come in the same box. In zeal for versatility, too often we lose the optimum for anything and everything. Sometimes, we stick ourselves with the barely adequate or barely adequate. Finding the ideal cross between the best tractor, the best dump truck, and the best sports car isn't an easy task. Too often we think we want that type of achievement, paying the unfortunate price of achieving nothing.

That is the price way pay for the theory of versatility. The truly comfortable 3-1/2 inch 12 gauge cannot be ultra-lightweight. We think we want that, though, so we now have lighter 3-1/2 inch guns that aren't remotely suitable for pass-shooting geese. At the same time, there aren't nearly light enough to be rationally compared to six pound 20 gauges, so they fail as responsive field guns just as badly as they fail in the goose pit. They are sometimes touted as deer guns, but they fail even harder when compared to fixed barrel sabot shooters for deer hunting.

When Browning first offered their 3-1/2 inch 12 gauge Gold, I bought one. It was surprisingly close in weight to my 3 inch Golds and it did cycle 1-1/8 oz. 1200 fps loads as promised. Yet, it was still a small amount heavier, needlessly, and the 3-1/2 inch chambered Gold didn't pattern as well as my 3 inch Golds did with 1-1/8 oz. target loads. I eventually decided I was stupid. There were many who quickly agreed with me. Some of them actually used shotguns as well. Not only did the Gold not pattern well with target loads, most 3-1/2 shells didn't pattern as well as the best 3 inch options-- and still don't. Too soon we grow old, too late we get smart.

That was quite a few years ago. The 3 inch Maxus Hunter patterned better with target loads than the 3-1/2 inch Maxus models. My 3 inch Vinci's patterned better than than a recently tested 3-1/2 inch Super Black Eagle II with target loads as well, "better" meaning more evenly with less patchiness and higher percentages with the same constriction chokes. My A390 patterns better than the tested 3-1/2 inch A400 Unico did with target loads as well. It is a trend that has established itself across several models and brands. Still, to this day, though I have tested 3-1/2 inch shells the best loads are buffered high-density 3 inch shells, not 3-1/2 inch shells, and I've never used a 3-1/2 inch shell on a turkey or a goose. Though the Browning Maxus and the Beretta A400 Unico both cycled 7/8 oz. loads, I've never bothered to use them for any serious clays efforts and certainly not for hunting anything and I likely won't-- there are far, far better performing options.

The Browning A-5 remains faster than most autoloaders, cycling at .12 seconds or faster as reported by Patrick Kelly. Faster than aimed fire is possible at different birds, faster than an 1100, faster than the faster Benelli M1 Super 90, the A-5 still is among the fastest autoloaders ever made and faster than most. It is largely a moot point, however, as the only way to get a gas auto to cycle faster is to up the bolt speed to a ridiculous level translating to more shock at the end of the stroke. How else? In order to eject a 3-1/2 in. unfolded length hull, the bolt must necessarily travel a longer distance to fully open and the same longer distance to close. If you want to travel greater distances in both directions, yet still cycle faster, excessive bolt speed is the predictable result.

It has been done, of course, the Beretta A400 does just that. Fortunately the folks at Beretta added the KO3 at the back of reciever to keep the gun from pounding itself to pieces. Its a good design, a clever design, but the combination of light weight and fast bolt speed doesn't make for soft shooting. It kicks more than the Maxus with target loads. So, in a bout of circular logic, the Michelin-man inspired KO device comes in, adding weight, bulk, and addressing recoil as load intensity increases with the compromise of more gun movement as the KO does its thing.

Beware the versatile shotgun. Marketing departments claim people want versatility. Like the crescent wrench, versatility might be a good thing to have if you don't know what you want. Versatility comes with substantial compromise and cost, though, two things many would rather live without.

Copyright 2010 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.

Custom Search