Shotgun Shells and Shotgun Chokes: like Laurel & Hardy

Since the days of Fred Kimble, it is hard to consider a shotgun shell without the notion of choke. They function as a team, not always as good of a team as Laurel & Hardy, but they are always a team nevertheless. Many combinations are abominable, horribly poor. It was the documented erratic results of shotshells and chokes that compelled George Oberfell (later known as part of Oberfell and Thompson) to write a treatise about it in 1949, an article that appeared in The American Rifleman in 1950. While Mr. Oberfell was perceptive enough to know that “the theory of probability applies to the distribution of pellets in a shotgun pattern,” a direct quote from his 1949 discussion, the results he experienced were so erratic it led him to a path of focusing on patchiness of patterns.

Not a good path, but part of the reason for it was his use of 150 patterns from fifteen shotguns, shotguns from five different manufacturers, seven payload weights, eight different shot sizes, and six different choking devices. By injecting all these variables, small wonder G. G. Oberfell found wildly different results. Both factory shotshells and chokes have the capability of being notoriously bad.

I. How Bad Can Shotshells Be?

For specific, well-documented examples of how poor some shotshells are, we can consider the findings of A. C. Jones in his 2010 book, Sporting Shotgun Performance. Dr. Jones found that the sphericity of some shot was bloody awful, with .020 in. out of round as common in some shells. Oval-shaped shot, shot that didn't roll well, shot welded together, a “Chef's Mix” of sizes and shapes is what he found. Andrew Jones described some of the shells as having many pellets that looked like Smarties candy. It doesn't take much to quickly realize that pellets of random sizes and shapes cannot possibly begin to fly the same and they don't.

No choke tube can hope to re-size or reshape our shot for us. If we want to blow stuff out of our barrels that looks like gravel, cubes, has the rings of Saturn, or looks like ink blots wildly inconsistent results are to be expected. The “normal distribution” doesn't work well when what we use shot to shot is abnormal and grossly misshapen.

Ammunition companies aren't solely to blame. We like cheap stuff, the cheapest stuff that goes bang. In order to give the consumer the cheapest product, quality control that costs time and money is naturally cast aside, due to the commodity-type pricing pressures that stress the shotshell market. Few people cut open shotshells and see what they are shooting, fewer still pattern their shotguns, so it all seems to work. Not always well, but if it doesn't make dollars it doesn't make sense.

II. How Bad Can Screw Chokes Be?

Screw chokes may be just as bad as shotshells, for several of the same reasons. Few folks measure their barrel's bores, much less their choke tubes. Eccentricity of choke tubes, poor choke installations, choke tube dimensions, and choke tube performance is not easily discernible with the naked eye. Remember the “dime test?” The idea was if a dime would not go into a 12 gauge barrel you had a “full choke.” Choke in a shotgun has always been performance-based, not dimensionally based, so the end result of the “test” establishes only that you had temporary possession of both a dime and a barrel.

Choke tubes in factory shotguns are often sourced items, the highest quality from the lowest bidder. The consumer drives this, as in most things, as the material a choke tube is made from is often unknown, much less who made it, where it was made, or how it was made. There was a time when mass-produced shotguns were patterned at the factory prior to shipment, including such models as the Browning A-5. It costs time and money to pattern an individual shotgun for P.O.I. and pattern percentage, and it also increases scrap rates. So, today, it is commonly avoided. Most consumers have made it clear they are unwilling to pay for it, so naturally they don't get it.

Andrew Jones didn't bother with the fifteen gun approach that misled George Oberfell, nor did he embark on the seven payload, eight different nominal shot size path that Mr. Oberfell used. Instead, he avoided factory chokes except for a fixed barrel, comparing full choke pattern percentages at 40 yards with Hull DTL300 U.K. #7-1/2 shot, the fixed tapered-parallel choke using the same load in U.K. #7 shot. Teague long taper chokes yielded 77.6% patterns, the fixed choke 75.2%, and the Teague short-taper choke 72.9% patterns at 40 yards. To have your O/U “Teagued” with three extended chokes is 327 pounds and requires reproof in the U.K. That's $537.79 is based on current exchange rates, plus freight both ways and the applicable VAT. Is it performance worth the price? Certainly, Dr. Jones and many other serious shotgunners think so. Nigel Teague is extremely highly regarded. The $600 arena for many American shooting enthusiasts is something that, let's say, is often resisted. The punter won't often invest in shotgun performance that way, so less than stellar performance is a virtual certainty.

What is the Solution?

All shotguns are individuals. Having tested and patterned so many shotguns over the years, it is impossible to miss. Even guns of the same make and model with consecutive serial numbers have been dramatically different entities in terms of performance. Barrel dimensions vary, choke performance is all over the map, fit is different, P.O.I. is different, trigger break weight is different, ability to cycle loads varies by individual gun. Every shotgun is unique, there is no question about it. Some are far more “unique” than tolerable.

The first step is of course to establish a base-line of performance, and a goal of where you want to be. There are are no absolutes. In fact, your factory choke-tubes may possibly give you what you want at shorter ranges or lighter pattern percentages. At longer ranges and when looking for higher percentages, it is highly unlikely. Yet, a negative cannot be proved. It is all performance based.

I. SHOTSHELLS

No one company offers all things all the time for all purposes. Yet, there are many excellent products out there and they have been mentioned on an “as tested” basis. The well-established fundamentals of consistency in shot diameter and sphericity, consistency in shot density, consistency in velocity all hold true.

Don Zutz, in an article named “Tricks Powders Play,” noted the vastly different and sometimes markedly improved patterns he documented with the use of Green Dot and Solo 1250 powders, obtaining full choke performance (over 70% @ 40 yards) with a “modified” choke all from the same same shotgun. Don Zutz further explored component changes in the “Hodgdon Powder Shotshell Data Manual” (1996) showing the changes in pattern percentage due to a primer change alone. By changing primers and chilled shot, his 35 yard pattern percentage averages changed from 73% to 88%, all with the same “modified” choked gun and 1-1/8 oz. payloads. A shotshell itself is a system.

Accuracy and consistency are considered synonyms in firearms, shot shells are not exempt from this generalization. As John Haviland wrote several years back in the American Rifleman, “Patterning your shotgun is as important as sighting in your rifle-- until you do it there is no way to tell where your gun shoots and how it really performs.”

II. CHOKE TUBES

I've consulted and worked with and for many firearms manufacturers over the years. Engineers and marketing folks tend to get along like hogs on ice, an understatement if anything. When it comes to choke performance, it cannot be considered known until it can be shown. As is the case with shotshells, there are several reputable choke tube manufacturers out there. I've not used them all, by any means, but I have used a goodly portion of them for many years.

The choke tube and the shotshell are the two primary tools we have to obtain the patterns we want, neither of which require any permanent modifications to the gun. Kim Rhode, eternal international shooting champion, phoned me a few days ago. Kim was the youngest member of the U.S. Olympic team in 1996, where she won the Gold in Double Trap in Atlanta. That made Kim the youngest gold medalist in Olympic shooting history. Kim followed that with a bronze in the 2000 game in Sydney, winning the Gold yet again in 2004 in Athens. Women's Double Trap was dropped from the Olympic games, so Kim changed sports. At the 2008 games in Beijing she won the silver in women's Skeet. Right now, she's off to Conception, Chile the end of this month for the World Cup. Kim uses choke tubes.

Kim uses custom tubes that throw the largest effective spread at the ranges she shoots, consistent and repetitive ranges. In Kim's case, it is both talent and hard work. She shoots essentially every day, 500 – 1000 shots per day. It is something like 320 or so shooting days per year, something along the lines of one quarter of a million shots per year, every year. Talent, dedication, and hard work combine to win. Let's just say that using choke tubes doesn't seem to be holding her back.

Ed Lowry worked for Winchester-Western div. of Olin from 1945-1973. Mr. Lowry held a B.A. in computer science from Western Washington University, along with M.A. in mathematics. He also became a member of the faculty at W.W.U., and moved on to become an independent ballistics consultant thereafter. In his article “Properties of Shotshell Patterns” from 1990 (American Rifleman), Ed Lowry memorialized the testing ordered by John Olin and the results obtained. It was the search for “patchiness” that concerned John Olin, the result being that 250 patterns were analyzed from Improved Modified and Full choked guns, with #2, 4, 6, and #7-1/2 shot, all 1-1/4 oz. payloads. The pattern percentages varied from 35% - 75%. No firm evidence of excessively large holes was found, though Lowry reported that the results were similar to the Oberfell and Thompson results.

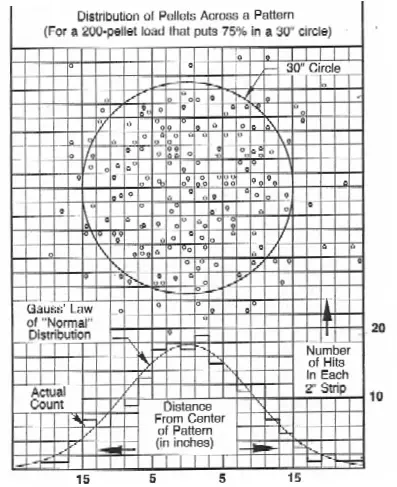

The most useful by-product, as Lowry called it, happened during the development of the Mark 5 shot collar, invented by Merton L. Robinson, manager of the Winchester test ranges. It showed the Gaussian nature of a patterns as a very close approximation. Noted by Journee in 1902, it now became a far more useful tool with more uniform shot and launch velocities. This became part of the basis for Lowry's later contributions, that rank today as some of the most important tools in the science of shotguns.

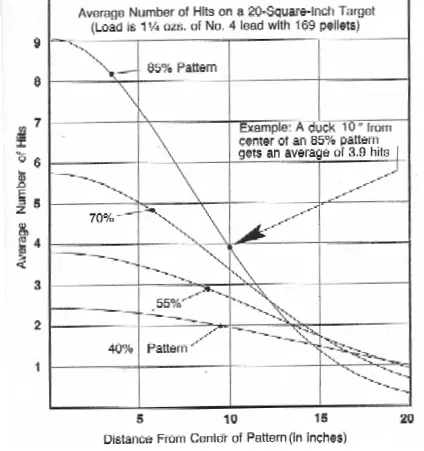

Above, Ed Lowry was better able to precisely predict pattern performance by realizing the "Normal Distribution" of properly loaded ammunition.

Normal distribution as applied by Ed Lowry and his team to mallard ducks, taking into account pattern offset and pattern percentages. More relevant than percentages alone, Lowry shows how many hits to the 20 inch vulnerable area can be expected when the shot cloud reaches the game using both pattern percentage and the target's distance from pattern center.

What to look for in choke tubes is related to what we look for in everything else: consistency of materials, quality of materials, strength of materials, quality of machining, and quality control. The person best-qualified to know what ranges shots are actually being taken at is the individual shooter. That's why there is no substitute for patterning your individual shotgun at the ranges you intend to shoot at with the exact shells you are going to use. There are no shortcuts.

In the normal course of testing and evaluations of shotguns and shotshells, I use both factory-supplied chokes and Trulock Precision Hunter Extended choke tubes. Precision Hunter Extended tubes are blued 17-4 PH stainless steel. 17-4 PH stainless steel is a metal typically used in oil refining, chemical processing, and the aerospace industries. The 17-4 family of stainless is considered to have an outstanding combination of high strength coupled with good corrosion resistance. It gains substantial strength through heat-treating and it withstands corrosive attack better than any of the standard hardenable stainless steels and is comparable to Type 304 in most media. 17-4 PH has a density of .280 lb. per cubic inch with a melting point of 2560 – 2625 degrees F.

I don't care for colored or bright stainless tips to my barrels, the blued Precision Hunters look much better. Looking down your muzzle in search of notches isn't a good practice. With extended tubes, you know what choke you have in the gun and they protect the crown of your barrel as well. For the serious shooter, the fellow that wants to get the most out of his shotgun, the consumer advantage is obvious: you get a lifetime warranty with a new Trulock choke. Want a smaller pattern? Want a more open pattern? No problem, you can exchange your new Trulock within 60 days for a different constriction, or get a refund if you choose. No one in the entire industry does that for you, except George Trulock.

III. PATTERNING

I can't say I enjoy patterning shotguns. It is a requisite step, though, just as John Haviland proclaimed. I'm not nearly clever enough to know just by looking at a shell or choke tube what the pattern is going to be. Both have to be used together, otherwise it is again Laurel without Hardy.

Hunters and shooters, always a fun-loving and innovative lot, spend a lot of time trying to short-cut the system. Reading breaks, the dime in the barrel, “patterning” at water, snow, or “one shot patterns” that are just as useful as one-shot groups out of a rifle are just a few examples. We can shoot at 20 yards to try to predict a 40 yard pattern. It doesn't work well. Dr. Jones noted that a 30 yard pattern was more representative of a 40 yard pattern than possible with a 20 yard pattern. The only thing that best represents a 40 yard pattern is a forty yard pattern just as the thing that best represents a 200 yard group from a rifle is a 200 yard group.

It takes a minimum of five shots at a specific range with a specific shell, choke, and shotgun to establish a baseline. Many have suggested ten shots as being better, and so it is. Representative sampling dictates the larger the sample size, the better the resolution. Recent tests have confirmed this, such as those by R. A. Giblin and D. A. Compton at the Holland and Holland Shooting Grounds in 1994. Relying on only three shots from a 'Quarter Choke' could produce results from 25 - 62% was their finding. Nevertheless, five shots is a workable, practical, and meaningful baseline.

Kim Rhode likely doesn't have to shoot 320 days a year to be outstandingly good. Perhaps she could slack off to a couple of hundred shooting days a year, and drop down to relatively “light shooting” of 175,000 shotshells per year, I don't know. But Kim knows, being your best is just that, and you don't get a gold medal in international competition for just being good.

So it goes with patterning, by comparison a very easy, if not tiny amount of effort. Since the only direct contact we have with the majestic birds we honor and hunt is the patterns we throw, doing the best job we can isn't a lot to ask of ourselves. Best of all, it is largely a one-time task. When we have discovered the best and most appropriate tools for our applications, there isn't much reason to change. Being more successful just makes hunting and shooting sports more enjoyable and more satisfying, so the rewards just end up going to ourselves.

Copyright 2011 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.

Custom Search

Custom Search