Rules of Choke Tube Constriction

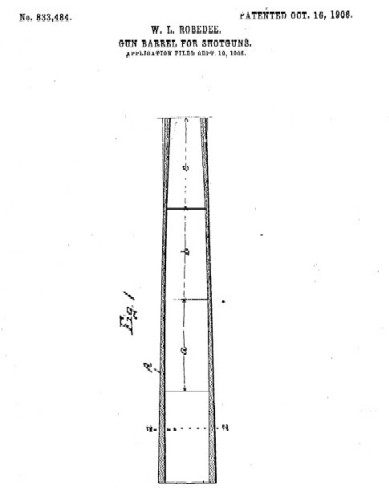

While we might think high percentage patterns are something new, that's not exactly the case. One hundred six years ago, William. L. Robedee achieved over 90% forty yard 30 inch patterns with his progressively tapered shotgun barrel, patented in 1906, compared to 75% from conventionally choked barrels with the same constriction.

I. Background

While there are no standards or rules for constrictions in choke tubes, there should be. No other component of a choke tube makes more sense or has such a clear effect on pattern diameter. Over the years, all kinds of observations and theories have been set forth. Few make any sense, much less pass the test of being sharable data. We all like claims, mysteries, and pretty graphs, though.

Part of the problem is the subject matter itself. What we have tried to do is apply exactitude to something that is intrinsically inexact. Back in January of 1956, Col. E. H. Harrison published "A ‘New’ Method of Evaluating Shotguns" in the American Rifleman, describing the superior German method of evaluating patterns from 1893. The patterns were segmented into 100 parts; the targets called "100 field targets." It was an extremely precise method of evaluating patterns; found to be too precise to be of value due to shot to shot variations. The Germans used a 75 centimeter circle at 35 meters range. While it gave tremendous data at that 35 meters range, it did little to show what pattern performance might be at all hunting ranges. The Germans went back to work, resulting in a huge body of work assembled and finally approved back in 1937.

John Brindle determined, it is not possible to have an effective spread with a 12 gauge 1-1/8 oz. shotshell larger than 25 inches across at any range. That calls into question the value of a 30 inch circle trying to define patterning performance. Still, you have marketing attempts shamelessly referring to the “critical 30 inch kill zone,” with large diameter shot, although there is no such thing. Don Zutz commented on the “tightening effect” of certain propellants on patterns, particularly Green Dot. With a small sampling, all kinds of conclusions can be reached, the same with cherry-picking of data. That is of course, the problem, as what is often desperately sought whether there is data to support it or not.

Shot itself is inexact. Flight characteristics of hundreds of pellets, colliding with themselves and the wind, pellets of varying sizes, various velocities, varying eccentricities, and varying densities makes for potentially quite a random event. What is the sphericity of the pellets in your shell? What is the muzzle velocity, really, of the next shot? How consistent are your shotshells over the next 500 rounds? No one knows, of course. Since we don't know, it is all the easier for a manufacturer of a shotgun (or shotshell) to say anything. All you have to do is say words to the effect of “We believe it is the best patterning thing you've ever seen” and away it goes.

II. Past Results

While all kinds of claims and ad-brags are continually made, little has foundation. If you think global warming is confusing, a subject matter studied by actual scientists, then what chance does a shotshell pattern really have? They are are so inconsistent, by nature, that one pattern is meaningless. It takes five, ten, or even more patterns to give a reasonable base for comparison. The frustrating thing is that we are hoping one shell, the next shell, is the shell that drops the turkey, yields a dead in the air pheasant, or breaks that piece of clay. Not the next five or ten shots, the single next shot. That is another problem with patterns, as they are all past performances, not future results.

III. What Doesn't Work

Forcing cones, backboring, cryogenics, changes in harmonic vibration: none of these interesting, long touted areas have been shown to do anything substantive. It isn't easy to prove a negative, so a clinical disproving is hard to come by as well. Although, Neil Winston (and others) have shown that elongated forcing cones and backboring have both thinned patterns and produced lower velocities with Perazzi and Remington test guns.

The human factor and the placebo effect is invariably at play. As long as we persist in trying to read breaks, there is little hope. How often have you heard the lament that, “Hey, I used my new choke tubes and my scores went down!” Where would we get the idea that a choke tube makes us a better shot? If you have ever bowled, your score isn't the same every game . . . even though you use the same ball. If a baseball infielder muffs a grounder, is it usually a “bad glove”? Wide receiver drops the football, well . . . bad football? Like anything else involving humans, we all have better personal performance days than others. The good thing is, it is hard to overdose on placebos.

IV. What Does Work

We do know what does work, and we do know that accuracy and consistency are synonyms. We know that perfectly spherical shot behaves more consistently than malformed shot or odd shapes, we know that buffering improves pattern percentages, and we know that higher velocity loads promote more open patterns. We know that larger diameter shot yields higher percentage patterns than smaller shot, which is of course a mixed bag as larger shot means less pellets for the same payload.

We know that wad design affects patterns, with both spreader loads that clearly work and non-slit wads that pattern more tightly with less constriction than slit wads. We know that the best patterns are produced by both high-quality shells and high-quality chokes, you can't have the best patterns without both.

V. Why Constriction Matters

More density than you'd want for wingshooting and a smaller pattern diameter than you'd want as well. This target was produced with a tighter constriction than you might think as well. It is the George Trulock Heavyweight #7 solution for wild turkey, a dedicated purpose choke tube.

The difference between the barrel inside diameter and the smallest choke inside diameter is the constriction. A constricted end of the barrel is what choke is, back to the days of Fred Kimble and the “choke bore barrel.” When it comes to “improving patterns,” improving means smaller diameter and therefore tighter patterns, as in “Improved Cylinder” and “Improved Modified” creating smaller diameter patterns than their standard cylinder and modified counterparts. It mattered when the notion of choke was popularized by Fred Kimble and it mattered when William Robe patented his 90%+ pattern percentage shotgun barrel.

Even though such products like Federal Black Cloud and Federal Heavyweight turkey loads relay on the non-slit style of wad to get patterns with less constriction than a conventional wad, constriction remains important. These two loads, though wioldly divergent, actually need more constriction to get the tightest patterns, not less, as George Trulock has discovered and shown.

Though "improving" a patten means a tighter pattern, historically, it rarely is what the goal is. The goal, is of course the largest effective pattern, not the smallest, for the specific ranges and applications. An "improved modified" level of performance is no improvement at all in American Skeet, it is the opposite of what close range shooting with high pellet counts requires.

Still, the marking on a choke tube or on a barrel means nothing specifically, it doesn't even mean a precise constriction as measuring some factory choke tubes can quickly reveal. It still sends us to the patterning board, where the solution is to start with a mild constriction choke and increase the constriction until we have the largest diameter pattern that we feel is an effective pattern for our use, with that specific shell, in our specfic shotgun.

Copyright 2012 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.

Custom Search

Custom Search