Pheasants Past 50 Yards: 20 Gauge Style

Pheasant shell and choke combinations are invariably a compromise. If we knew the ranges we are taking roosters at, it would be a whole lot easier. If cock pheasants were clones, identical in age, weight, and feather thickness . . . that might make it a bit easier as well, but they aren't.

To complicate matters, we don't even know the size of the target in advance. If a pheasant jumps quartering away, we have one size of target. A perfect crossing shot is a rare happenstance around here, but it happens. "Incoming pheasant" also happens, but it is rare. A crafty old rooster may get up wild, flying low, head down, wings pumping away. In that case, the theories about pattern density and penetration dissolve in a hurry. The target is now only 25% or less the size of that wonderfully exposed crossing shot, so our goal of three or four pellets in the vitals just became more difficult. Sure, the head and neck are considered part of the kill zone, but that is of no comfort when all you have is tailfeathers and pheasant butt as the target. A pellet in the head is fine, but we aren't likely to get it the Texas heart-shot way on a wild ringneck. That's why there are no quick, cozy answers to this, we have incalculable variables.

Pattern density and pellet penetration are the two primary factors in wounding ballistics of a pellet on upland game. Yet, the density required is contingent on target size, a big variable, and the penetration desired for a crossing shot compared to a rump or back presentation aren't remotely the same thing. Preserve birds, fresh from the pen, may be no harder to take than pigeons. The classic pigeon load is 1-1/4 oz. of hard #6 shot, to no one's surprise. Mature, wild roosters can be a different story altogether. The best wingshooting pattern isn't the smallest pattern. Quite the opposite, it is the largest effective pattern, as we want something for the dinner table as well. There is this thing known as “pattern offset,” another way of expressing the hunter's aiming error, and that too is a variable that calls for the largest effective spread, not the smallest.

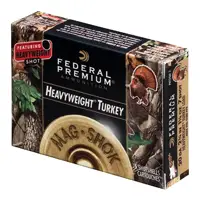

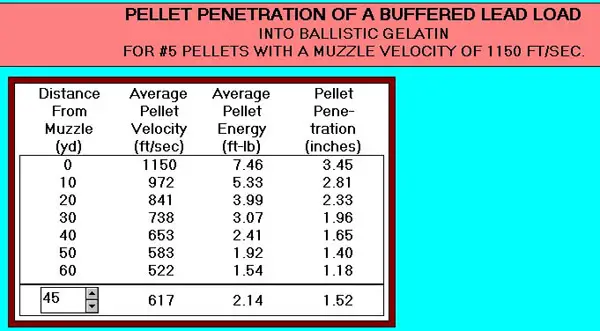

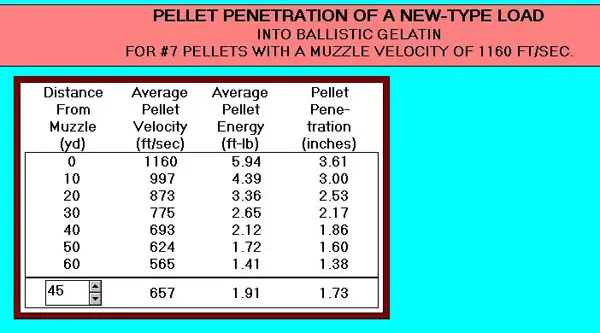

The Federal Heavyweight #7 20 Gauge load, introduced as a whopperdoodle 1-1/2 oz. three inch turkey load, is now available in a 2-3/4 inch version with a 1-1/8 oz. payload as depicted above. The average pellet count for this new 1-1/8 oz. load is 250 pellets. The exterior ballistics are the same, exceeding #5 lead, due to its comparatively better density of 15 grams per cubic centimeter. What follows is a penetration comparison of #5 buffered lead against Federal Heavyweight #7.

This load has a lot to offer the wild pheasant hunter. As it is a 2-3/4 inch shell, it is appropriate for all 20 gauge shotguns that are steel and no-tox rated. With 40% less recoil than the full-payload Federal three inch turkey load, it makes that second shot faster and is easier on your gun as well. The pellet count of 250 is better than a 1-1/4 oz. payload of #5 lead (approx. 213). More pellets with better penetration, actually about 17% more, with naturally less recoil than the heavier payload as well. It's less recoil, better penetration, along with a substantially higher pellet count. Not only that, the Federal Heavyweight #7 is a no-tox shot material, so you can use it where lead is (wrongfully) not allowed as well. We patterned these shells from several guns. The Browning B-80 / Trulock Improved Modified Precision Hunter extended choke combination is shown on this three minute video.

Pattern density does indeed improve with a smaller exit diameter Trulock choke, a Trulock PH Invector "Full" and "Turkey" both gave tighter patterns beyond the .595 in. Improved Modified choke I settled on. There is a reason for not going beyond the 25 thousandths nominal constriction IM tube. It is still all a compromise, so what helps at 52 yards a bit cuts down effective spread at shorter ranges and produces a pattern that is overly dense. As I enjoy eating what I hunt, though a quick, clean kill is what I want . . . I also don't want stew birds. Just because a load like this is 52 yard capable doesn't mean I'm going to intentionally stretch shots. Most of the birds last year were taken between forty and forty-seven yards. It's nice to have the ability to whack them at fifty yards or so with the right presentation, but that hardly means it is a scenario to purposely strive for.

As always, the most important factors in shotgun performance are shotshell and choke. Like Laurel and Hardy, it is the combination that counts. For no-tox 20 gauge pheasant hunting, this combination makes everything else look pretty sad by comparison. From a practical standpoint, it exceeds even the best 1-5/16 oz. #5 lead buffered twenty gauge loads I've tested at 50 yards.

This is no such thing as "right or wrong" when it comes to pheasant loads. There are far, far too many variables to even begin to suggest that. What I can say is that this combination is an outstandingly good one, is quite worthy of your consideration, and this is what I'll be using this year for wild pheasants. Pheasant and wild rice under glass, here we come.

Copyright 2011 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.

Custom Search

Custom Search