The Eternal Battle of Gas versus Recoil Autoloading Shotguns

A common area of discussion regarding autoloading shotguns is the “which is better” debate, gas-operated or recoil operated. Naturally, anyone that can read a catalog will be informed that several autoloaders are currently “the most reliable!” Actually, the most reliable repeating shotgun is the pump, as shell function is removed from the equation.

The notion of “reliability” needs a little amplification, as being able to cycle a lighter load doesn't necessary make a shotgun more reliable, it just means it can cycle a lighter load. Reliability when neglected isn't reliability either. It isn't rational to find that our car isn't reliable because its six year old battery no longer holds a charge.

One way to look at autoloading shotguns actions is simple: it is either gas-operated, or it isn't. If it is gas-operated, there are going to be gas ports in the barrel to help the ejection process. That is all autoloading shotguns can do, help eject the shells. What operates the shell lifter (a.k.a. elevator or carrier) and closes the bolt is going to be a spring, or combination of springs: springs already compressed by the bolt movement. Nobody wants an unreliable shotgun that I know of, so the truly fussy or problematic autoloaders are no longer made or never were strong sellers. Sadly, some of the best autoloaders ever made are no longer available, either. I'll start by going through a few gas actions.

The most influential gas-operated shotgun came along in 1963, the Remington 1100, a trap model of which is shown above. It was the Remington 1100 that began the gas-operated gun era, long before folks like Beretta figured out how to make a competitive autoloader. Most don't seem to remember that relative newcomer Beretta didn't even make a 20 gauge autoloader until 1971, the A301. The Remington 1100 was good-looking, affordable, and fit most shooters well. While now categorized as a dinosaur, it was anything but in 1963. Most shells fired were 2-3/4 in. lead loads, and while now the poor ability of the 1100 to shoot extreme varieties of loads is part of its downfall, it wasn't that way in 1963. A 12 gauge target load was 1-1/8 oz. at 1200 fps, a field load was 1-1/4 oz. at 1330 fps, and that's all a 12 gauge shotgun needed to function with. The 1100 did that and it did it with no adjustments, unlike the Browning A-5.

Gas-operated

autoloaders need cleaning to either be reliable or to handle pipsqueak

loads. So, as long as you know how to clean a gun, there was little problem.

The number of shells a gas-operated gun can function with depends on ambient

conditions, the type of shells used, and the individual gun. Some 1100s

would go 200 rounds or so, some 300, but it didn't matter. You followed

the manual, cleaned the gun after shooting it, and most folks don't run

more than a case of shells though their gun in a day, anyway.

The next significant step in the food chain was the Beretta 300 series,

most notably the A303 and Browning B-80 models. Now, you could go 1000

shots before cleaning (like the B-80 owner's manual suggests),

alloy receivers made the guns lighter, and the stocks were shim-adjustable

for height. The idea was to use a 2-3/4 in. barrel for 2-3/4 in. loads,

popping on a 3 inch chambered barrel for heavy loads. A good idea and

a simple one, although it didn't take consumers long to buy 3 inch chambered

guns and complain that their 1 ounce reloads wouldn't cycle.

The Beretta A390 introduced the secondary gas bleed in 1994.

The next step in the cycle was the Beretta 390 (1994), offered with a 3 inch chamber and adding a secondary gas bleed to the front of the 303's barrel housing. Surprising, it was only made, originally, until 1998 or so. Clever folks like Rich Cole made replacement sets of secondary gas springs, a set of five, so now the 390 became the most versatile autoloader ever made, cycling down to 7/8 oz. loads with the stiffest Cole spring and with the lighter spring, could handle the heaviest 3 inch loads without shaking itself to pieces.

Browning took a different tact, using their “Activ valve” in the Browning Gold that was released in 1994 along with the Beretta 390. It was, by far, Browning's most successful gas autoloader introduced until then, and finally offered 1 oz. and up no adjustment load versatility. Apparently worried that people couldn't figure our how to put the secondary gas spring back in the gun, Beretta followed with the harder to clean 391 and Browning extended the Gold into Winchester SX3 and Browning Silver models. The Brownings are easier to clean without any special tools, the Berettas seem to go longer without cleaning, the Brownings are softer shooters, the Berettas have better factory triggers. Browning Golds had speed loading, Beretta's were mostly shim-adjustable, only some Brownings were. Gas operated autoloaders have been reliable, durable, and have cycled a reasonably wide variety of loads ever since the Beretta 390 and the Browning Gold. Reliable if you cleaned them regularly and cleaned them properly, that is. Since then, autoloading shotguns have gotten more expensive, generally uglier, and 3-1/2 inch chambers are there whether you want them or not. The Beretta 391 is no more, the A400 line taking its place, while the Maxus is the flagship Browning gas auto, and the 3-1/2 in. only Remington Versa-Max seems like it is going to be around for a while.

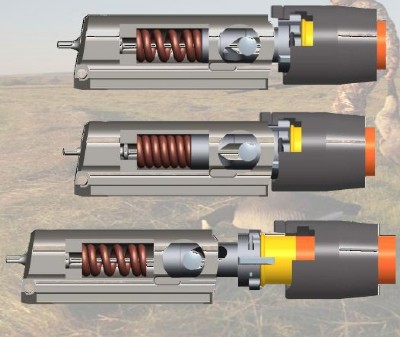

Above, the latest spring thing: the "Kinematic Drive" action from Browning's soon to be released "A5."

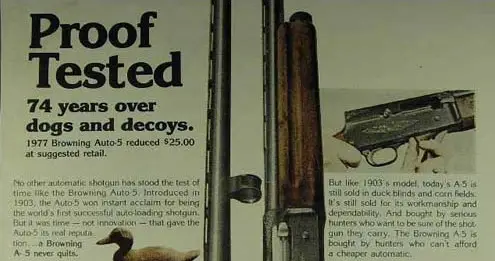

Recoil operated autoloaders were defined by the original, the Browning A-5, that for decades has no competition of any significance. They do require less cleaning, as with no gas system there are no barrel ports to monitor or any gas components to soak and scrub. You also don't have gas blowing out around the barrel, magazine tube, or various exit points. A recoil operated autoloader is essentially a spring gun. Barrel movement from the A-5 moves the breechblock rearward, compressing springs, and the springs do the rest. The Bruno Civolani action uses a split bolt, with a spring in the center. Rearward motion of the gun compresses the spring from rearward, floating bolt body. The bolt spring initiates the rest of the sequence. The Benelli brand group of Beretta has largely had the recoil operated autoloaders to themselves. The Franchi AL-48 is based off of the Browning A-5, the various Benelli's based off the Civolani action, with the Stoeger and Franchi “inertia” marketed guns completing the picture. Browning's new A5, dubbed the "Kinematic action,” seems to owe a great deal to the Civolani action as well.

Gas actions can be soft shooters, as the gas piston that is propelled rearward has mass and also generates recoil, or thrust, but in the opposite direction. Total recoil remains the same, in the end it is zero sum, but gas actions can break up the sharpness. Recoil-operated guns can reduce felt recoil as well, as long as you can adjust the action speed as in an A-5. We don't like adjustments, though, so in the case of the Benelli guns they do what they do. They tend to be lighter than gas guns, so naturally lighter guns kick more. They can't kick more than a fixed breech gun, that isn't a possibility, but lighter guns kick more.

Gas guns don't have to be soft shooters at all: Beretta has proved that. The violent action of the A400 allows cycling with light loads, but between the rapid gas action and the light weight, they can be impressive kickers. It is hardly a coincidence that the “Kick-Off” hydraulic stock is so heavily touted: light guns kick. It shouldn't be a real shocker that the Remington Versa-Max is a soft shooter, it isn't because it is a gas gun. It is an eight pound gun with a thick recoil pad, so soft shooting is to be expected. One of the softest shooting 12 gauge shotguns that I own is a steel receiver Browning B-80. No recoil pad, just the factory rubber buttplate. It is hardly a soft shooter just because it is a gas gun. It weighs 8 lbs. via Timney trigger gauge. We can't stray all that far from basic gunweight before looking to happy fun time stock gimmicks and so forth. More than a few people has rightly asked, “If these gas guns have so little recoil, then why the wunder-pads, the barrel ports, the pogo-stick stocks?” Good question. Gas operation alone does not eliminate recoil. Gun weight and gun fit can hardly be completely ignored just because an autoloader is gas operated.

As

to what action can handle the widest variety of loads, the gas action

can . . . somewhat, but only if properly maintained. For most commonly

used shotshell loads, fast 1 ounce loads and up, there is no difference

worth being obsessed with. One type isn't clearly superior to the other.

Based on six million rounds fired per year, Zeke Hayes of Hayes and Hayes

outfitters calls the Benelli Montefeltros and Beretta 390s the most durable

autoloaders, one recoil-operated and one gas, with the Browning Gold next

in line. Both recoil and gas actions can be thoroughly competent. Gun

fit, weight, handling, aesthetics, trigger quality, and shell handling

prowess of an individual model will likely away you in one direction or

the other, but not solely based on action type.

Copyright 2011 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.

Custom Search

Custom Search