Gas-operated Vs. Recoil Operated Autoloaders, Part III

As

published in an Ugo Beretta patent, gas-operated autoloading shotguns

can have their problems.

“The

high recocking speeds translate in high stresses and, consequently, in

a decrease of the working life of the shotgun components. In the whole,

this results in a short duration of the same shotgun. In the more modern

gas-operated shotguns, it has been successfully attempted to obviate the

problem of the high recocking speeds by adopting shutter or self-compensating

valves, which are able to exhaust the excess gas associated to the firing

of the cartridges having a higher gram weight. However, such valves, or

venting systems, involve an increase of the mechanics and the costs for

the shotgun. Furthermore, the gas-operated systems require a constant

maintenance, since the gas which is vented tends to foul unburnt solids,

which have to be removed after firing a number of shots.”

But,

inertial actioned shotguns have their issues, also mentioned in the same

patent:

“The

low recocking speed, which is intrinsic of the inertial shotgun, may be

a problem, especially when the shotgun frame has a high mass, and the

fired

cartridge has a low or very low gram weight. The low recocking speed translates

in a low shell ejection promptness and a high risk of jamming. Furthermore,

the operation of such type of shotgun is highly affected by the user's

behavior, particularly by the type of reaction which the user opposes

with his/her shoulder to the shotgun stock.”

From the less than enthusiastic description in the Ugo Beretta patent, it sounds likes Mr. Beretta doesn't much care for autoloading shotguns at all. We might be under the impression that shotguns are designed to be strong and to last long, but they certainly aren't. They are designed to have fun with, for the most part, and that means light enough weight to be carried between the hands and swung effortlessly. Nor would they need to be strong, for a shotshell is a very, very low pressure cartridge compared to even a .22 rimfire short.

Winchester claims that the SX3 fires 12 shots in 1.442 seconds. While the barrel pressure is only a fraction of that time, the only time the shotgun is under any stress, vibration, or has parts moving at all is less than 0.1202 seconds per shot. While we might think that 50,000 rounds is a lot of shooting, that's only 120 hours of operation, or 5 days. In industrial terms, the life of an autoloading shotgun is pathetic. In automotive terms, in consumer appliance terms, in electronic terms, an autoloading shotgun is also unacceptable. Could you bear the thought of replacing springs every day in your refrigerator, air conditioner, or personal computer? It is a design effort not based on extended life at all, for you probably would want to go hunting with a sump pump or a water heater, or something that looked, handled, or swung like either.

The cost of shooting isn't just in the shotgun, for a case of cheap Estate target loads runs about $55, or twenty-two cents a shot. That 50,000 rounds even if only target loads is $11,000 and there are clay targets, range fees, and so forth on top of that. Prices vary, but a round of skeet may cost you $5, or $10,000 for those 50,000 shots. Now we are at $21,000, more in some areas, more for sporting clays, much more for hunting ammo, and so it goes. Of course, we do squander some pesos on food, water, and transportation as well.

Those

looking for a snappy answer as to which type of action is the mythical

best won't find much comfort, for some of the most heavily used shotguns

on the planet are Argentina outfitter's rental guns, and twenty gauge

more often than not. The quest for “the most reliable” autoloading

shotgun won't be happy with the answer based on experience: http://randywakeman.com/Most_Reliable_Autoloading_Shotgun.htm

. The inertial Montefeltro and the gas-operated A390 are the two winners,

according to Hayes & Hayes.

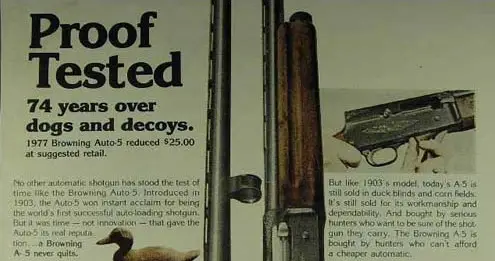

The

Original: The Automatic-Five of John M. Browning

The grand achievement of the A-5 was not that it was the best of any breed:

it was a new breed, the most remarkable thing about it is that it worked

at all. The shotshells of the day were variable, so it wasn't about firing

different loads interchangeably as much as it was being able to use different

brands of shells at all, for shells varied by brand significantly. That

it was so good that it had no competition for fifty years makes it all

the more remarkable. Though John Browning left us in 1926, twenty years

later no one in the world had a competitive product to the A-5 and when

the Browning patents expired, the autoloaders that had some popularity

(Remington 11-48, Franchi AL-48) were cheaper versions of the Browning

action.

Faster-cycling than either the Remington 1100 or Benelli (Bruno Civolani) actions that came along over sixty years later, it has been used to win at the Olympics, live bird championships, and national skeet championships as well. It lacks the low recocking speed of the inertia action and gas fouling is no issue. But, cost of manufacture was an issue, using 3 inch unfolded length shells required a whole new receiver, and so would have the use of 3-1/2 inch shells which, in part, helped to end the reign of the A-5 as a production gun.

The Current Inertial Actions

While the basic action function hasn't changed much from the Bruno Civolani design acquired by the then Benelli Motorcycle Company, variations continue to appear as in the Benelli Raffaello (above) which adds another recoil-attenuating system to this 2950 gram (about 6-1/2 lbs.) autoloader. This one is called the "Progressive Comfort." The inertial action remains simple, cheap to make with very few parts, and low maintenance. The action itself kicks like a fixed breech gun, there is no way around that, it cannot handle the wide load intensity spread of the better gas systems, but Comfortech and now the Progressive Comfort stock add-ons try to soften the jolt. They can be fabulous hunting guns, but really cannot compete with the better heavy, smooth gas guns for constant clays-only work. It is guns like this and the 6-1/2 lb. Browning A5 "Kinematic" inertial offering that have further cemented the demise of the 16 gauge. If you use them with the classic 16 gauge type loads, 1 oz. for target / doves and 1-1/8 oz. for hunting, you'll probably be delighted. If you like a steady diet of heavy payloads, you just might find yourself wishing for a heavier gas gun or that older Automatic-Five.

The Current Gas Actions

While at one time an autoloader that actually worked was quite an accomplishment, we sometimes decisionally-challenged shooters continue to confound manufacturers. We always want what physics does not allow: light guns with no recoil. Some clays shooters claim "3/4 oz. is all you need," while some hunters lament that 3-1/2 inch shells don't hold enough steel and that 4 inch magnums would be more effective. It has created quite a mess, for gas auto 12 gauge that functions with 7/8 oz. loads, at least for the most part, has excessive bolt speed, vibration, and wear with 1-7/8 oz. or 2 oz. loads. It normally isn't comfortable, either, so now we have the pogo stick "springy stock things" that started with the the patented Hydro-Coil that was featured in Sports Illustrated (Sept. 9, 1963), claimed to reduce recoil by as much as 85%, and became a standard option available from Olin-Winchester.

A) Non-compensating Gas Actions

While the Remington Model 58 required user adjustment from "low brass" to "brass loads" with the Dial-A-Matic cap, shooters sometimes left it at the "low Setting" and promptly blew off the cap via 1-1/2 oz. "Baby Magnum" loads or similar. The most popular non-compensating actual was the Remington 1100, introduced in 1963. Back in the day when only two 12 gauge loads were common, 1-1/8 oz. load for targets / light birds and 1-1/4 oz. for pheasants / ducks, it did just fine. The Beretta A302 / A303 / Browning B-80 actions did better, going three or four times as long without cleaning. While also non-compensating, bolt speed is regulated by a barrel change: use the 2-3/4 inch barrel for target loads through 1-1/4 oz. loads, the three inch chambered barrel for 1-1/4 oz. 1330 fps and heavier loads.

The Beretta M4 and Remington Versa-Max, using twin gas pistons are claimed to be self-regulating, but obviously are not. They claim to be self-cleaning, like most gas shotguns. Like all gas shotguns, you of course have to clean them . . . some more often than others, that's all.

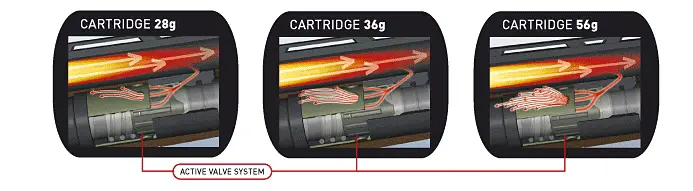

B) Compensating Gas Actions

Many gas guns required a manual adjustment or a barrel change to operate with different ends of the load spectrum through 3 inch loads. The Beretta A390 (above) added a secondary gas bleed to the 302 / 303 system, so the 3 inch chambered guns could handle 1 oz. target loads on up right out of the box with no adjustments. Apparently aware that shooters would be quick to gripe about jamming with pipsqueak loads, the secondary gas bleed springs factory supplied were overly stiff. Cole Gunsmithing fixed that for the 390 (and the later 391) by offering spring kits so you could tune your bolt speed and resultant ejection distance to your loads.

In 1993, the Browning Gold was released with its "Active Valve," as shown above. With springs integral to the piston itself, it has proved to be a softer shooting action than the Beretta releases. Still, to get the most out of it F.N. has released different pistons for the heaviest of loads.

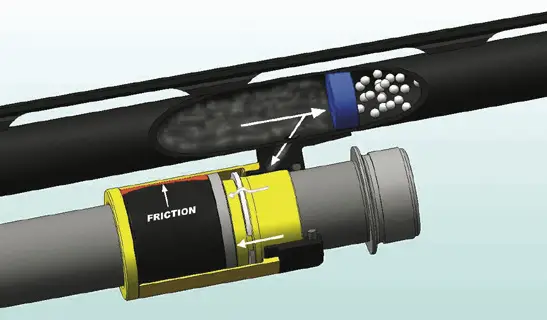

In 2003, FABARM released its Pulse Piston system, using the gas to expand the elastomeric seal of the piston against the magazine tube to control piston speed. That does away with secondary gas bleeds and associated springs altogether. The result is a gas action with friction compensation hybrid.

Copyright 2013 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.