Killing a Deer with a Bullet

Photo courtesy of Ian McMurchy

This article like should likely have been entitled “Penetrate, Rip, Smash, Crush, Tear, Destroy: the Delicate Art of Deer Hunting” which is a bit more descriptive of the matter at hand. Wounding ballistics as applied to muzzleloaders, slug guns, handguns, and centerfire rifles has lived in the dark ages for centuries. Part of the problem is just human nature: we want simple, cozy, mindlessly quick and snappy answers to complex questions. We ask what a “good” gun is, a “good” bullet is, and a “good" cartridge is all the time with loose, open-ended questions. Is the .323 “Super-Snorter” any good? Hey, is the Remchester Model 8675309 any good? Is the Lasermaster Extreme a “quality” bullet? Words like quality and good are so vague as to be meaningless. Yet, we keep asking, though not much is learned from this type of non thought-provoking, Simple Simon type of discussion.

Next, we have the notion of “kinetic energy” as being a factor in wounding. It isn't. “Kinetic Energy does not wound,” is the statement from the FBI. It has nothing at all to do with field effectiveness and is not a usable or valuable number at all. Kinetic Energy does not wound and kinetic energy does not transfer. You'd think that by now, the dangers of "kinetic energy" would be so well known if they existed that sudden blasts of kinetic energy would be regularly listed as cause of death in autopsy reports. Perhaps old washed-out tombstones would read, "Here Lies Good Ol' Fred: Hot Nasty Blast of Kinetic Energy Knocked Him Plumb Dead." Grieving families around the world be asking, in lieu of flowers, for a generous donation to the Kinetic Energy Prevention Foundation chapter near you. It hasn't happened quite yet: medical science has missed it. It is very easy to miss something though, particularly when it does not exist as a wounding mechanism.

Ammo manufacturers publish the numbers, of course, but they rarely say what the relevance is, because there is none. As shown by the works of Theodor Kocher, more recently by Dr. Martin Fackler and Duncan MacPherson (“Bullet Penetration,” Copyright 1994, 2005 by MacPherson) kinetic energy quickly changes into heat, and is in no way a reliable barometer or index of wounding. It apparently is a reliable thermometer, though. A 200 grain jacketed bullet fired into a 1 ft. x 2 ft. x 12 foot tank of water with 2300 fpe increases the temperature of the water .002 degrees F. It doesn't injure or wound and none of us has enough ammo to directly warm up a cup of coffee, much less a full pot.

Dr. Fackler commented to me, “The KE fallacy is so pervasive that it needs to be corrected as often as possible. The arrow is a good example: I think it helps to drive the point home if you mention how much KE a hunting arrow has (a 500 grain arrow traveling at 200 ft/sec has a KE of 44 ft. lb.). Thus the largest game in the world (including elephant) is hunted and killed with a projectile having only about 2/3 the KE of a 22 Short bullet. That should give pause to even the most ardent KE advocates.”

Certainly, Martin Facker, M.D., is not suggesting that everyone should go elephant hunting with a .22 short or an arrow, but it well illustrates the peculiar notions we have about energy, power, knock-down, and all the other colorful phrases that have no basis in reality. A lot of things can kill, your family doctor can help you with that. When it comes to deer hunting, though, like any other endeavor to make valid comparison you need basis, not just interesting phrases.

There are, of course, interesting pictures of bullets in ballistic gelatin primarily designed to show pretty bullets. Penetration in calibrated ballistic gelatin, unlike kinetic energy, is a useful gauge of penetration in soft tissue, finally. The “finally” part is credited to Dr. Fackler, who insisted that ballistic gelatin be calibrated to be meaningful. Prior to the 1980s, it wasn't.

What we should all keep in mind is what ballistic gelatin lacks. There is no airway, breathing, or circulation. Ballistic gelatin has no spine, no rib cage, no shoulder bones. Ballistic gelatin does not bleed, has no individuality, no will to live, and does not instinctively run. There is no particular health of ballistic gelatin, no adrenaline, it leaves no blood trail, and it behaves the same whether you shoot it from the front, back, sides, above, or below. While game animals are not clones, the whole idea of calibrated ballistic gelatin is to measure it as a clone, as an identical test medium and tissue simulant. This does not invalidate ballistic gelatin for what it is; it does however illuminate what it is not and cannot possibly be. You can't gut-shoot ballistic gelatin and you can shoot all day without affecting the central nervous system of ballistic gelatin, as it has none. You can't spine it, stun it, frighten it, spook it, kill it, or revive it. There isn't much point in trying to kill it. Ballistic gelatin chili, ballistic gelatin jerky, and ballistic gelatin roasts would all be a bit on the bland side.

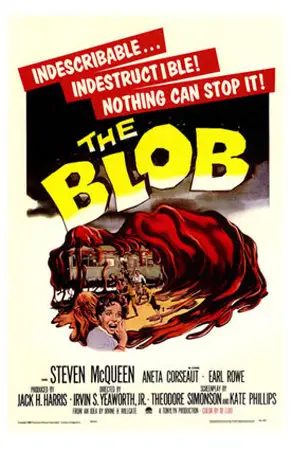

Yes, indeed, 10% ballistic gelatin is a very, very long ways away from the deer family of thin-skinned game. With no skin at all, ballistic gelatin is just not a worthy opponent. With apologies to Steve McQueen (and Dr. Fackler) the Blob would be a far more interesting tissue simulant than ballistic gelatin. While still sorely lacking in many deer-like features, it makes up for it with personality. At least it was pink and had the propensity to suck life out of humans, making the inclination to shoot at it understandable.

Hunters in general have no proper training in understanding wounds, wound dynamics, or incapacitation resulting from wound trauma. As a result, the fanciful tales and remembrances of folks like ivory poacher John Taylor and the colorful (if a bit wacky) notions of Elmer Keith are parroted and regurgitated to present day. Jack O'Connor, a far more thoughtful, perceptive, and self-critical man, gave us far more practical, well-reasoned information from the sportsman's perspective.

It was Jack O'Connor that denounced the sloppy type of hunting that left more game in the field than was brought in. Flipside, it was Roy Weatherby that, in order to tout his “magnums,” intentionally gut-shot African plains game. Perhaps the low-point of wounding ballistics ineptitude was when Roy Weatherby suggested that with a fast enough bullet, you wouldn't even have to actually hit a game animal to quickly kill it. A tiny, high-energy bullet just whizzing by in the general vicinity of the animal would create such a great atmospheric shock-wave that the animal would fall over dead. Actually hitting the animal could be an unnecessary inconvenience. Even William Shatner ballistics are better than that.

While Roy Weatherby felt the future of ballistics would not require the hunter to actually hit the animal, William Shatner using the standard issue Star Fleet Type II Phaser (c. 2266) was still forced to actually aim at and connect with his target about three hundred years later.

It was the energy notion that gave rise to the touting of the .220 Swift as the ultimate killer, the cartridge that dropped animals like the hammer of Thor. It took a while, but finally common sense took over and the .220 Swift was exposed for what it always was: a varmint round, hardly the ideal deer cartridge.

Hunters are no better or worse today than they were in Jack O'Connor's day. The lost animal is blamed on the bullet, the gun, the scope, everything but the hunter. It was wrong then and it is generally wrong today. Darrin Bradley performed a recent study on deer hunting. Over 1792 hunts with 34 hunters, only 16% of those hunters that got a shot at a trophy whitetail buck killed the animal. For any hunter with a conscience, numbers like these should prove troubling.

It is numbers like these that make the argument of “ruining too much” meat more than laughable. Ruining meat can hardly be considered an issue compared to wasting the entire animal. Destroying internal organs is not exactly a concern, for few hunters actually eat internal organs and in many areas it isn't a healthy practice. No one I know looks forward to fried lung for breakfast.

In the words of two of the participants in the 1987 Wound Ballistics Workshop, “too little penetration will get you killed.” More to the point here is that too little penetration may not kill, meaning a lost animal. Every year, there are lost animals that need not be. There will never be a handy guide to deer hunting projectiles of any great, absolute meaning as all deer are individuals and no two wound profiles are exactly alike.

There are some things that we can do to minimize the potential problems, though, even if those looking for guarantees and absolutes will never be satisfied. I've conducted my own, informal survey over the last ten years as to the circumstances surrounding lost animals. There are some trends supported by fundamental wounding ballistics to watch out for. The reason for lost animals is hard to measure with exactitude, as the animals are lost and only the recollection of where they thought they were hit and at what range exists. For animals that are recovered the next day, or go 400 yards, though medical autopsies are generally not done, there is a better idea of what took place.

Here

are some of the more common issues.

1)

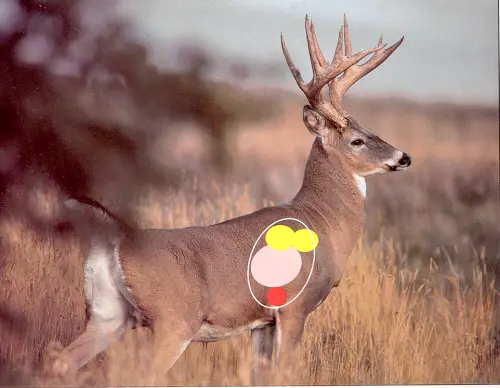

“I shot him in the shoulder.”

The scapula, or shoulder blade, is not a vital organ at all. A fractured

or broken shoulder is hardly a good wound, a wound that will leave a blood

trail with certainty, or a wound that means instant incapacitation at

all. Bullets deflect easily, particularly with deformed noses at different

angles. Both water and the ground cause ricochets, much less something

as unpredictable as a shoulder blade. Bone fragments may cause ancillary

damage, but that too is unpredictable. Intentionally hitting shoulder

as an entry wound is risky business and a poor target. It may work, but

so can a .220 Swift. Staying off the shoulder is really good advice unless

you know better. Vital organs are engorged with blood. No matter what

bullet you are using, no animal can live very long with no lungs or no

heart, and they don't. A deer can live a very long time with a smashed

shoulder, though, and a three-legged deer may be faster than a four-legged

deer. A deer (and many other mammals) can live a very long time

with one lung as well.

2)

Sectional Density

The sectional density of a bullet isn't hard to measure. It is just the

mass of the bullet divided by the diameter squared. Bullets of the same

design with better sectional densities penetrate better. A low sectional-density

bullet can spell trouble where a high sectional bullet will not. An old

saying, the further the range the heavier the bullet has a lot of merit.

It certainly was the case with the 45-70 Government at nearly two miles.

In the general case, the better sectional density bullets don't come in

a weight range, what is meant is "heavy for caliber."

3)

Beware of Bullet Over-Drive

Sure, you are no doubt familiar with the saying, “Speed Kills.”

In deer hunting, speed may have the effect of killing your bullet performance

more than it kills the animal. Bullets do have design parameters and velocity

limits. The same bullet with adequate integrity at moderate velocities

may turn into a varmint bullet if the strike velocity is high enough.

The better 50 yard bullet and the better 250 yard bullet do not always

come in the same box.

4)

Pretty Bullets Don't Mean Pretty Terminal Performance

We tend to like pretty, sexy looking bullets. We also like pretty fishing

lures in eye-catching packaging. The problem with eye-catching fishing

lures is they are designed to do just that, catch the angler's eye and

not the fish. We have a bit of the same issue with bullets. "Blaster

Wave Buckwhacker Elite Supreme Magnum Elite Plus" bullets sure

sound deadly, don't they? Problem is, they are often more deadly to your

wallet thickness than to a game animal. The most common example of this

today is likely the “polymer-tipped bullet.” Generally, a plastic

does nothing to terminal performance except impede expansion. Hydraulic

expansion of a bullet means fluid in the nose of that bullet, and something

like plastic inserted into a hollow point can only interfere with the

process, in no way helping or initiating it.

4)

Worship of Expansion

There is nothing wrong with expansion, but it is only one facet and an

expanding bullet may be the wrong choice depending on the specifics. Perhaps

you are familiar with the term of "Dum Dum" bullets? That was

a term spawned from the British Dum Dum arsenal near Calcutta, India,

where expanding soft point and hollow point bullets were produced for

the .303 British round. The Dum Dum became a generic term. Jacketed bullets

were used to cut back on bore leading, but the British noticed in Battle

of Omdurman (in 1898) that their Mark IV hollow point bullets were

more effective than full metal jacket rounds. So much so, that by removing

the jacket material from the nose of their standard Mark II FMJ they were

able to make improvised expanding bullets that created larger than bore

diameter wounds.

It was the story of a man, a woman, and a rabbit in a triangle of trouble. "Dum-Dum" bullets were fired in Toontown that were confused as to "Which way did he go?" in 1988's "Who Framed Roger Rabbit?" The Dum Dum Arsenal in Dum Dum, India was no cartoon, however, playing a real role in the production of expanding bullets for the .303 British service cartridge.

This didn't last for long, as the Germans protested the use of the Mark IV bullet and eventually we had the prohibition of expanding bullets in the form of the Hague Convention of 1899. The comparison was invalid back then, as while the expanding bullets did prove more effective in the .303 British versus the full metal jacket types. However, the expanding .303 rounds still produced wounds less severe than the cartridge the .303 replaced: the .577/450 Martini-Henry. The formidable .577/450 Martini-Henry service round was 85 grains of black powder pushing a 480 grain .455 diameter bullet at 1350 fps. In any case, the Hague Convention eliminated expanding bullets from proper warfare because they are "inhumane." As to the notion of military intelligence, we are left today with the opposite idea in hunting: full metal jacketed bullets are considered inhumane for deer, and often prohibited. No wonder the poor hunter is confused. The humane bullet in warfare may be considered inhumane when hunting and vice-versa. None of the "protests" about being humane proved genuine, of course, with the Germans having no qualms about introducing Mustard Gas in 1917. Suffice it to say for the purposes of this article the Hague Convention and Geneva Protocols are reprehensible horse manure.

Surgeon Major General J.B. Hamilton understood this long ago as he wrote in the British Medical Journal in 1898:

"Let me point up that if the Dum-dum be used, it, as a rule, will injure but one man, as when "set-up" its power of penetration rapidly ceases; if, on the other hand, a projectile covered entirely with nickel be employed, it will possibly pass through two or three men, and gradually "setting up" inflict great injuries on a fourth.

An admiral in command of the fleet would not hesitate to "ram" a battleship or blow her up with a torpedo, destroying perhaps 800 men in the operation, and would gain renown for the action; but if our War Office uses a projectile calculated to stop individuals, it is condemned as "inhumane"!"

Expansion is good to the extent that it can create a larger permanent wound cavity than a non-expanding bullet. However, an expanding bullet reduces penetration. Expansion is a good thing, but never at the expense of adequate penetration. When a bullet deforms or expands, we also have the "opportunity" for fragmentation and weight loss, meaning even less penetration than would otherwise be expected with expansion alone.

6) Over-Reliance on Lethality Values and Bullet Manufacturers

We like numbers, perhaps we like numbers a bit too much for our own good. A higher number is a better number, so it makes us feel good. I've done extensive load work-ups mentioning the majority of the lethality values. One load in particular shows all of the following:

Hatcher’s RSP = 120.4

A-Square Penetration Index = 41

A-Square Shock Power Index = 539

Tappan’s WAVE factor = 120.4

IPSC Power Factor = 665

Lott’s Estimated Effective Energy: EEE1=306 EEE2=1497

Taylor Knock-Out Value = 43.5

Fuller Index = 175

Matunas Optimum Game Weight = 1468 lbs.

Wootter’s Lethality Index = 306

Arnold Arms Relative Performance Index = 96

Elmer Keith Knockdown Factor = 95 pounds / feet.

Parker Ackley’s Momentum = 66.5

You might think that with all the above information there isn't much left to discuss? After all, this is a far more extensive set of number-crunching using established equations than you'll ever see for a load from any major ammunition manufacturer that I'm aware of. None of them are reliable, though. None of them take into consideration accuracy, shot placement, individuality of the deer, ambient conditions, or range.

We can hardly blame manufacturers for trying to stay in business. If it doesn't make dollars, it doesn't make sense. We have a "dumbing-down" of some of the literature, as in "CXP2" class loads. It is a horrible idea. We often have the usual drone of "think-skinned game" with a little cartoon of Bambi next to box, or on the box. Quickly checking just one major ammunition manufacturer for Bambi-suitable ("medium game") loads, I just found a 55 grain and 60 grain .223 Remington load advertised as suitable. Also suitable, suggested, and recommended for the same application is a .300 Remington Ultra-Mag with a 180 grain bullet. In all, over 400 different loads are cited as ideal for "medium game" accompanied by the deer cartoon. Whether you consider this a bad joke or just mildly amusing is up to you.

7)

Fear of Heavy Bullets

We don't like heavy bullets for our own reasons not involved in terminal

performance. We like flyweight bullets that mean less recoil at a given

velocity. As a result, we stay away from some of the better terminal performers

by choice. A 300 grain .44 Mag (.429 in.) bullet has a SD of .233. Some

think that is a heavy bullet. Yet, a 130 grain .270 Winchester (.277 in.)

bullet has a superior SD of .242.

With slug guns and muzzleloaders, our idea of a comfortable bullet to shoot again ignores sectional density, for a .452 diameter 250 grain bullet (normally fired from a sabot) has an extremely poor SD of just .175. Yet, we wonder why we might lose an animal if we hit bone? It isn't all that mysterious. The .45-70 Government, the standard U.S. Military round, drove the American Bison and the grizzly bear to extinction in a few short years. The common bullet was a .458 diameter bullet weighing 405 grains, for a SD of .276, making most deer rounds used today look very weak in the sectional density department. We shouldn't wonder why the .45-70 did so very well for so very long.

Even back then, the U.S. Military was looking for more. They found it based on the Sandy Hook Proving Ground tests of 1879, the .45-70-500 grain round that could produce lethal wounds at distances of 3,500 yards. At 3,500 yards, the .45-70-500 penetrated three one-inch thick oak boards. After smashing through the three oak planks, it then drove eight inches into the sand of Sandy Hook beach. While capable of more shoulder-smashing devastation than today's whitetail hunter seeks, we seem to have forgotten what we discovered 130 years ago.

IN CONCLUSION

While hunting terminal performance remains in its infancy from a scientific point of view, at least the way it is commonly understood, marketed, and practiced, there are several components we can consider to make better bullet choices and shot placement choices. There are few absolutes, few cleverly quick answers, and perhaps even less detailed information despite the untold millions of deer we have harvested.

Matching the bullet to strike velocity, shot placement, and what biology tells us is a vital organ can make us more effective in the field, which is the whole idea. Some of it remains the same as when Jack O'Connor wrote of it. The mature, seasoned hunter shows the wisdom and restraint to pass up a high risk shot, where the beginner rarely does. It is one of the many reasons it is called hunting, not just shooting.

Copyright 2009 by Randy Wakeman. All Rights Reserved.

Custom Search